THIS IS A SUMMARY OF THE MAIN LEARNING THAT I HAVE TAKEN AWAY FROM PART 4

PROJECT GAZE AND CONTROL

Reading On Foucault: Disciplinary Power and Photography by David Green (Exercise 4.1)

- I had not thought of photography as a mechanisms of surveillance to observe/and classify people in order to normalise disciplinary power.

- As Green suggests if this is so, we should develop alternative ways of working with photography.

The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes ((Exercise 4.2)

The seven types of gazes identified gives me something to reflect on I my work going forward:

- The photographer’s gaze: the camera’s eye which structures the image.

- The magazine gaze: chosen by editing for emphasis.

- The reader’s gaze: a reader’s interpretation, influenced by their experience & imagination.

- The non-western subject gaze: confrontational/distanced look/ absent gaze.

- Explicit western looking: which is unusual as westerners usually look off camera.

- Returned or refracted gaze: usually by mirrors or cameras

- Academic gaze: a subtype of the reader’s gaze.

It’s an interesting concept that some photographers are experimenting inviting viewers to interpret them rather than accepting the photographers gaze as their own. I will be more aware going forward of the interplay and relationships of the various gazes and their potential effect on the viewer, and the ambiguity in the work in particular.

PROJECT DOCUMENTS OF CONFLICT AND SUFFERING

Reading the articles ‘Walk the Line’ (Houghton, 2008) and ‘Imaging War’ (Kaplan, 2008( (Exercise 4.4) raises issues such as:

- How far should we go with publishing images of war and disasters?

- What images are suitable?

- Are there any lines to be crossed?

- Are the answers defined by ethic, commerce, respect for individuals or their families, politics, relationships between media companies and governments, or are they simply personal?

It is the photographer who must be mindful of the way the images may by used. I believe whether an image should be used or not I think, comes down to if using it adds impact to the story.

THE ETHICS OF AESTHETICS

‘Imaging Famine’ (Exercise 4.5) This research project in 2005 highlights issues that persisted in images of famine:

- Stereotypical images of victims

- Could positive images of people in need be presented?

- Can photographers provide images with context, understanding and explanation?

- Does immediacy enabled by technology cause simplified compositions?

- Can just one picture share a good understanding of issues?

- Are photographers simply image makers or do they have wider responsibilities?

To print or not to print (Exercise 4.7)

When choosing what to include in an image I would:

- Think about what I consider decent, is there consent?

- Consider privacy, is it a public occasion seems to be the crux of this

- Ask would the presence of the camera invite violence?

This was the first time that I’ve read The National Press Photographers Association, code of ethics (2017), in particular it states that “our primary role is to report visually on the significant event and varied viewpoints in our common world….the faithful and comprehensive depiction of the subject at hand”. When photographing as documentary I must remember this.

REFLECTING ON THE WAR PHOTOGRAPHS

Has made me consider topics such as journalist embedding, staging for cameras, rapid publishing, post camera manipulation and their effects on the quality of media images.

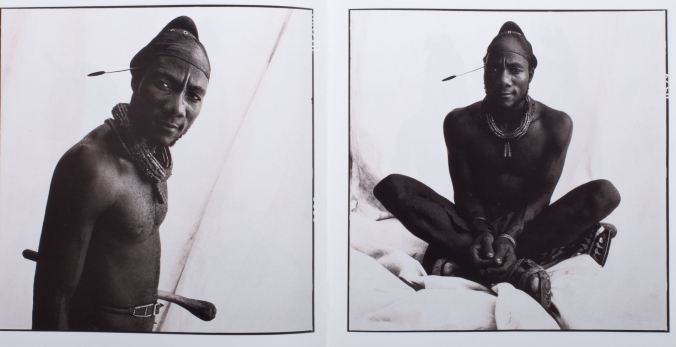

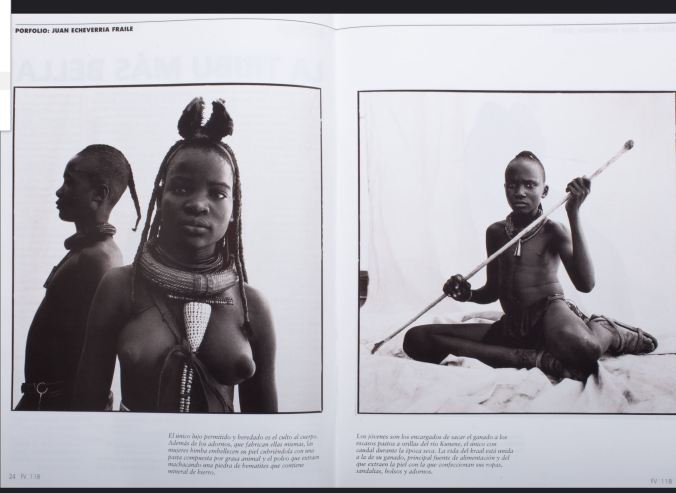

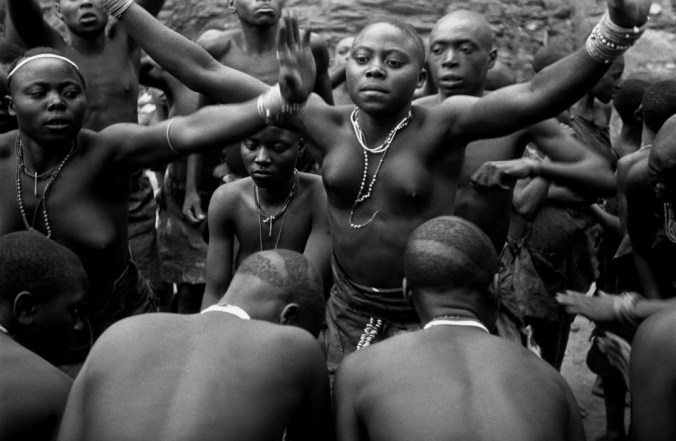

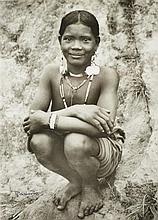

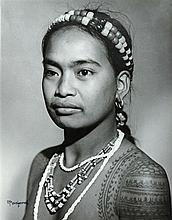

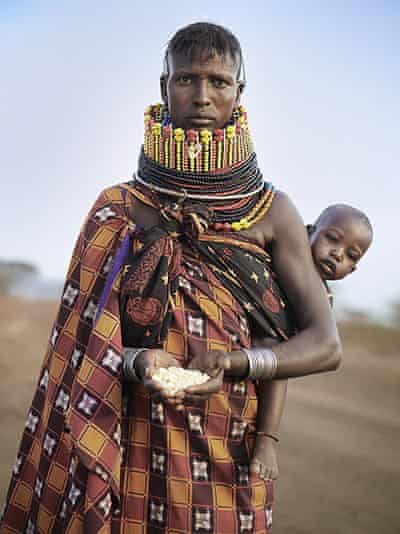

PROJECT POST-COLONIAL ETHNOGRAPHY

It was good for me to reflect on colonial and post-colonial world especially certain “traps” that have been identified:

- Nostalgia – Romanticism of primitive beauty

- Imbalances of power between photographer and subjects

- Disciplinary cataloguing and comparing

- Primitivism

- Decontextualising

- Infantising of non-industrial people

I was pleased to find photographer’s work such as David Ju/’hoansi Bushmen (2021), George Rodgers (En Afrique, 2016) and Eduardo Masferré (1909 – 1995) who had avoided most of these traps – I will now be alert to them when viewing such work again.