THe FSA project

Do your own research into the FSA project and the work of the photographers listed here and others. (Open College of the Arts, 2014:44).

The Farm Security Administration Photographic Project (1935-1942), the most famous of America’s documentary projects, was among President Roosevelts efforts to fight the depression as a rural relief effort. It began under the Resettlement Administration in 1935, that became the Farm Security administration (FSA) in 1937. Roy Stryker was the head of the historical section in the RA Information division and supervised roughly 20 people to make a pictorial record of the impact of the Great Depression on the people; his actual brief was to gather photographic evidence of the agencies good works and give these to the press (Marien, 2006:278) . Eighty thousand pictures were taken to “document the problems of the depression so that we could justify the New Deal Legislation that was designed to alleviate them” (Curtis, 2020:4).

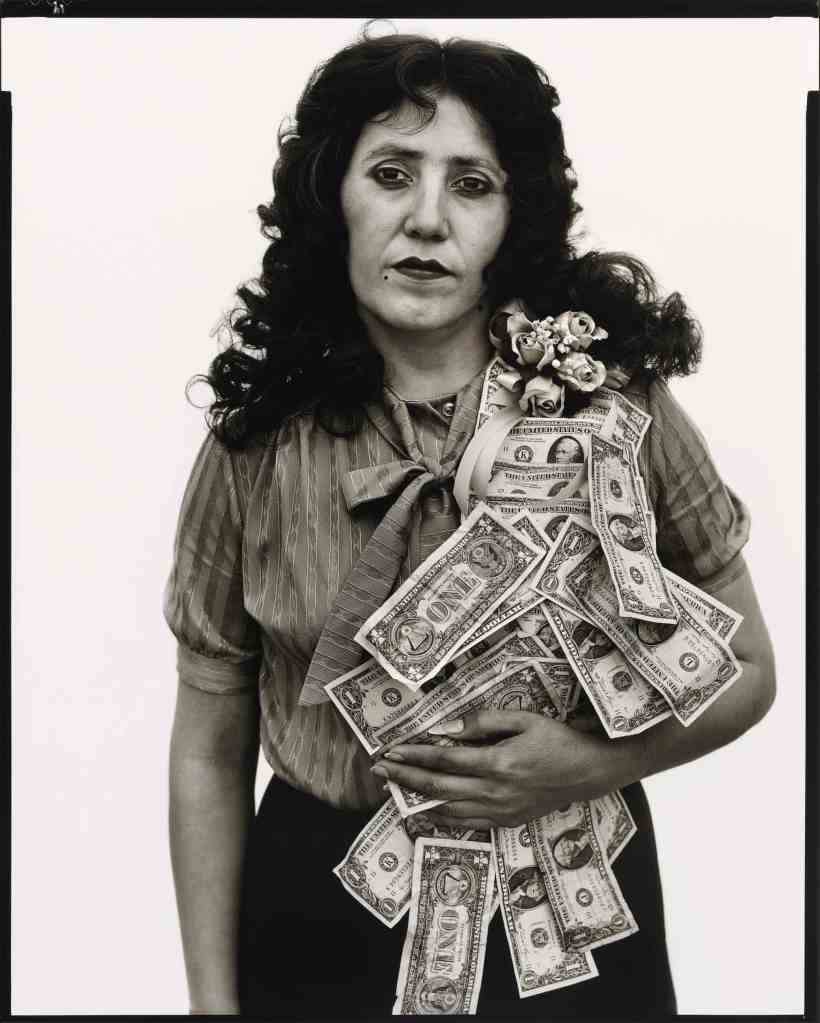

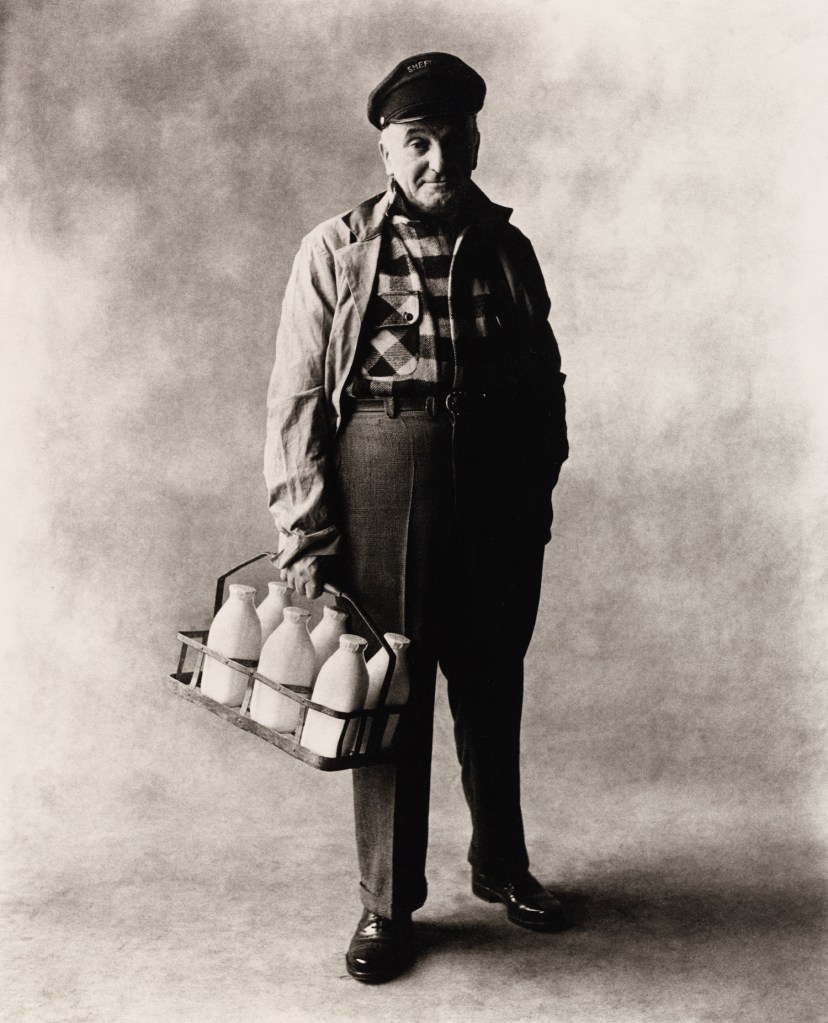

Stryker understood the value of making a visual record and said that he could show depression without showing social strife, for instance strikes, however to me many of the images do exactly that. I have researched many of the FSA photographers before, such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White and Arthur Rothstein, though I have turned up one or two new facts in this research. Walker Evans was dismissed after a year because his images were too uplifting and picturesque; whilst Rothstein was accused of fakery when he moved a Steer’s skull to make a better image and many of the photographers were charged with altering their photographs for impact. I had not heard before of Gordon Parkes and Esther Bubley, who were employed when the focus changed from rural to urban life, Parkes photographed the office cleaner and Esther Bubley women workers.

Ultimately many of the 175,000 images weren’t used especially if they didn’t fit Stryker’s objectives. Of the FSA photographers many such as Walker Evans, Paul Taylor and Dorothea Lange moved into gallery photography afterwards.

After my reading of Curtis’s piece below I am more aware that these documentary photographers posed as “fact gatherers” and were consciously persuading others.

References:

Curtis, J. (2020) ‘Making sense of Documentary Photography’ In: History Matters Making sense of Evidence series pp.1–24. (Accessed 29.6.20)

Open College of the Arts (2014) Photography 2: Documentary-Fact and Fiction (Course Manual). Barnsley: Open College of the Arts.Curtis, J. (2020) ‘Making sense of Documentary Photography’ In: History Matters Making sense of Evidence series pp.1–24. (Accessed 29.6.20)