EXERCISE: DISCONTINUITIES

Make a selection of up to five photographs from your personal or family collection. They can be as recent or as old as you wish. The only requirement is that they depict events that are relevant to you on a personal level and couldn’t belong to anyone else. Using OCA forums such as OCA/student and OCA Flickr group, ask the learning communities to provide short captions or explanations for your photographs. Summarise your findings and make them public in the same forums that you used for your research. Make sure that you also add this to your learning log (Open College of the Arts, 2014:22).

My message to forums:

Hi all

Please would you help me with an exercise in part 1 Documentary for which I have selected 5 photos from my personal album and ask you to give short captions or explanations for them. Later I’ll summarise the effect that the discontinuity (absence of time/context) seems to have on their interpretation.

Many thanks in advance

Niki

These are the captions that my peers suggested:

Image 1:

- Can you spare any change for the phone box?

- Penny for the guy

- I thought all your good deeds were for free – now you want a tip?!

- Here’s your dinner money, so run along now

- And I thought my outfit was tight.

- Thank you, love, you’re a diamond.

- It’s since they recruited more police officers.

- Back in the day, saving the world from villains paid good money.

Image 2:

- Riding piggyback.

- Lee wished he could take a sandwich to school like the other kids.

- Magic beans.

- I wonder if he knows he is on the way to the market?

- Down back there.

- Security has a nose for these things.

- Bringing home the bacon.

Image 3:

- Greta sat patiently in the canoe and hoped she would make the conference in time.

- Gatecrasher.

- Just all bums and legs.

- Colin decided being an extra on Hawaii Five-o wasn’t worth it.

- I told you water doesn’t run up hill.

- “This kite is rubbish. Who sold it to you?”.

- All hands on hull.

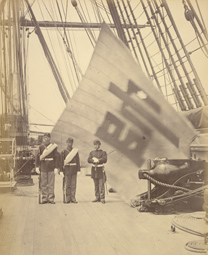

Image 4:

- Horseman of the Apocalypse Outfitters.

- We come in peace.

- The invisible men.

- This gig’s not worth losing our heads over.

- Invisibilty was an unexpected side effect of corona virus survival.

- Everyone saw right through them.

- Sadly, nobody was able to pick out the infamous “Invisible Man”. in the hastily arranged identity parade.

Image 5:

- Daily bread.

- Elliot Erwin always makes riding a bike in France look so easy.

- All this for a loaf of bread.

- Up hill struggle.

- One competitor was a Head in the uphill section.

- He was determined to make it to the scissor shop if it killed him.

My reflections:

John Berger in the chapter Appearances (Berger, 2008:60) explains the difference between what an image shows/evidences and the reason it was taken. Berger maintains that every photograph contains two messages, that of the event photographed and one about the shock of discontinuity, the chasm between the moment of the capture and the time we view it; though we rarely register the second message. It is this discontinuity that gives images ambiguity which all have as they are all taken out of continuity. As Berger explains, in general meaning is not instantaneous or discovered through facts but is found through connections.

The personal photographs that shared with the forums and the responses to them confirm his ideas:

- On a street in Basingstoke. In this image my viewers sought to make meaning out of what they could see: money changing hands and a man in a superman outfit; in the event they were not too wide of the mark as “superman” was collecting money for something, there was no more to the image than that and the silliness of a man dressed as superman out of any context.

- At a market in Northern Vietnam. Again meaning is made from even from the little being shown; most viewers correctly commented on it in the context of a market, and the bizarreness of the situation to a westerner, which was spot on.

- A surf boat upturned at the end of a race to release water taken on board. The context in this was harder to fathom, as it required inside knowledge I think and the captions given it were amusing but were a distance from the actual truth of events.

- Street artists in Rome. Again the context here would be hard to guess and the captions given were amusing but general.

- Steep hill in Lincoln, aptly named. Two viewers attached meaning to it based on the Hovis advert which was in a similar setting albeit some years ago. Others were able to attribute meaning to it based simply on the evidence of a steep hill. Interestingly because the context was easier/more familiar captions were slightly more serious.

So the captions ascribed to my images show that when an event in an image is simple to decipher because clear context is given a reasonably sensible interpretation can be made, however when less context is available then interpretations fall wide of the mark as the discontinuity of the image blurs understanding.

References:

Berger, J. (2008) Ways of Seeing [Kindle Edition]. From: Amazon.co.uk (Accessed on 30.4.20) UK.

Open College of the Arts (2014) Photography 2: Documentary-Fact and Fiction (Course Manual). Barnsley: Open College of the Arts.